Tatas, Adani, Ambanis in scramble for super app

- The groups plan to take on well-entrenched players like Amazon, Flipkart, and Paytm by merging their offline businesses with e-commerce initiatives.

- India’s top business groups, such as Tata, Adani, and Reliance Industries, are scouting for acquisition targets to offer additional goods and services under their “super app” umbrella.

- The conglomerates are planning to offer personal loans, travel bookings, and movie tickets to create a consolidated digital platform that will support their existing offline businesses, say bankers.

- Tata, Adani, and RIL have millions of customers across their verticals. The super app will just bring them under one umbrella and help cross-sell products. They are looking for those digital companies that are not in their current portfolio and offer a ready customer base.

- The Adani group is the latest to join the bandwagon by acquiring a minority stake in travel portal, Cleartrip, from Walmart-backed Flipkart group. Like Tata and RIL, the Adani super app will support its offline businesses. The group had in September acquired a 10 per cent stake in CSC Grameen eStore, a rural-focused grocery store, to offer its range of food products, including Fortune oil, to rural customers, say bankers. The group aims to add 1 billion customers to its digital platform by 2030.

- The Tata group, which recently bought several e-commerce companies, is also on the prowl. Tata Digital, which plans to launch TataNeu super app, will offer all goods and services from the Tata group companies, including airline and hotel bookings. The recently acquired e-commerce companies by the group, including BigBasket and pharmaceutical product delivery firm 1MG, have been integrated into the super app.

- The Tata group employees have been currently given access to the super app to check for any last-minute issues.

- Tata Capital, which has a significant retail and corporate loan portfolio, is also expected to chip in by offering loans to its super app customers.

- Mukesh Ambani-owned RIL is investing heavily in building its super app ecosystem and will offer services from movie ticket bookings to travel tickets. It is also planning to integrate the database from its latest acquisition, JustDial, to help customers connect with small businesses around them.

- Analysts are forecasting a 50 per cent market share for RIL in the online grocery market by the financial year 2024-25, with a 30 per cent market share in overall e-commerce.

- This translates into $35 billion e-commerce GMV (gross merchant value) for RIL by FY25, with $19 billion in grocery and rest by non-grocery. Overall, we expect retail Ebitda (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) to grow 10 times from current levels by FY30.

- The new entrants would make a dent in the market share of Paytm, Amazon, and Flipkart that are offering a range of services to their customers, including payment gateways and air ticket bookings. Paytm is currently the leading payments platform in India with a gross merchant value (GMV) of Rs 4.03 trillion as of March 2021. But with cash-rich conglomerates entering the market, it will be interesting to watch how the current players retain their market share.

- What is a Super App and how to build one ?

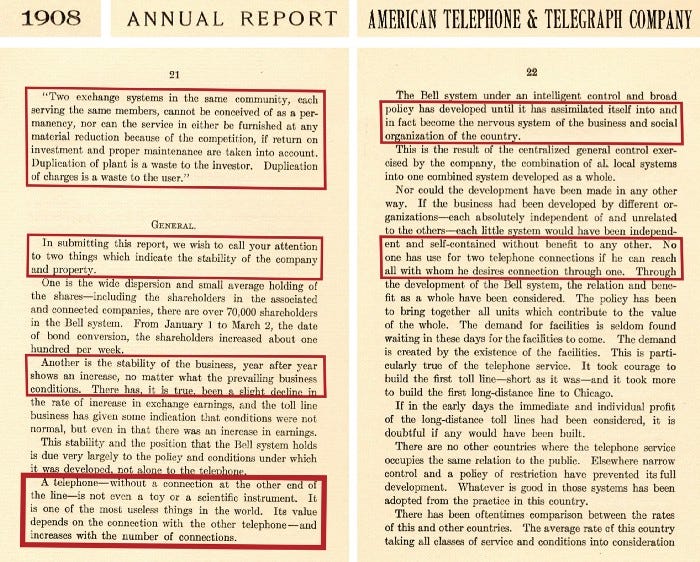

70 Percent of Value in Tech is Driven by Network Effects

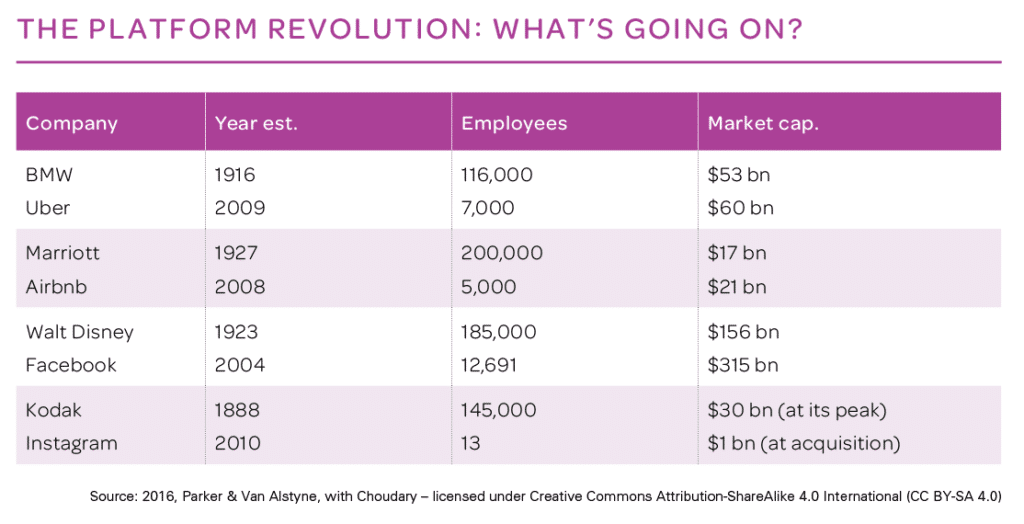

- The Big 5 — Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon — are hitting all-time high valuations. Airbnb is worth more than Hilton in the private market. Uber is worth more than GM. Spotify and Dropbox IPOed in 2018, with Slack and Didi Chuxing on an IPO track.

- It’s fitting they should all be mentioned in the same breath, because other than Amazon, their business DNA is amazingly similar.

- They are all network effect businesses. And it turns out that most of the outsized returns of companies since 1994 have used network effects.

- If you know the playbook, you shouldn’t be shocked at these companies’ rapid growth. But it’s surprising how few people know the network effects playbook. Many still confuse it with viral effects. Many know it’s important, but don’t know what it means.

- You might wonder what the secret sauce of these tech companies’ rapid growth and high valuation is. The simple answer to that is Network Effect. A network effect is when another user makes the service more valuable for every other user. In traditional market, more customers would drive more units produced. That would spread fixed cost across units and lower average cost per unit. While, in digital market, more units consumed would create more value to the network and would increase value per unit. That’s why network effect is also known as the demand-side economies of scale.

Definition — A product displays network effects when more usage of the product by any user increases the product’s value for other users (and sometimes all users).

- Once a company achieves a network effect, users won’t find much value in competitors’ smaller networks, which makes any business hard to catch and an existing player would achieve economic moat.

- Similar to positive network effect, there is also a negative network effect. A negative network effect occurs when welfare decreases with the addition of more users. i.e. network congestion, lock-in or switching cost and conflicts of interest.

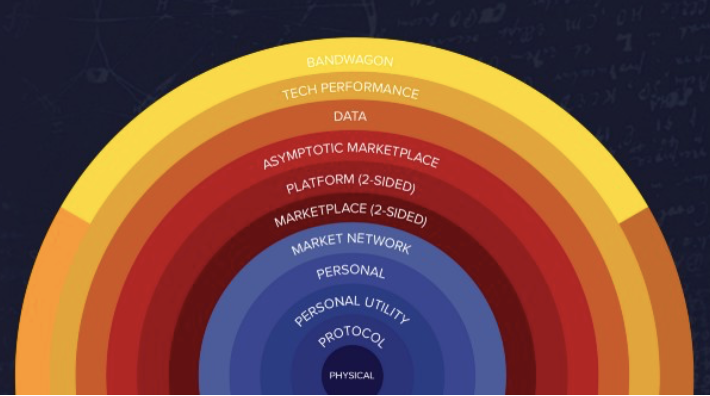

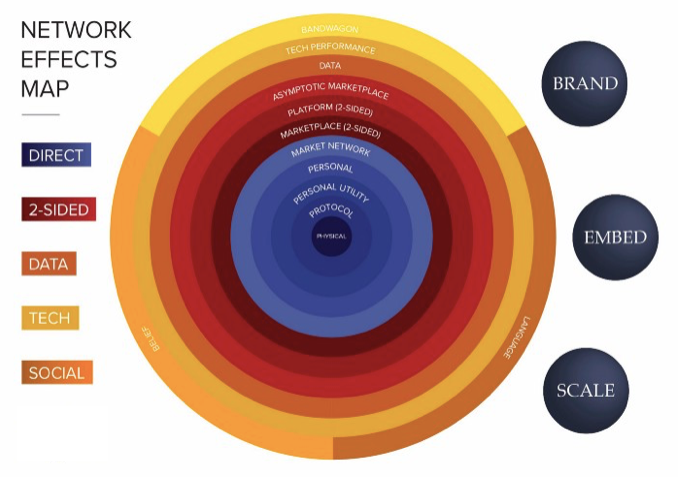

Types of Network Effects

There are different types of network effects and their behaviors are different.

“Not all network effects are created equal — some are stronger and tend to produce more value than others.”

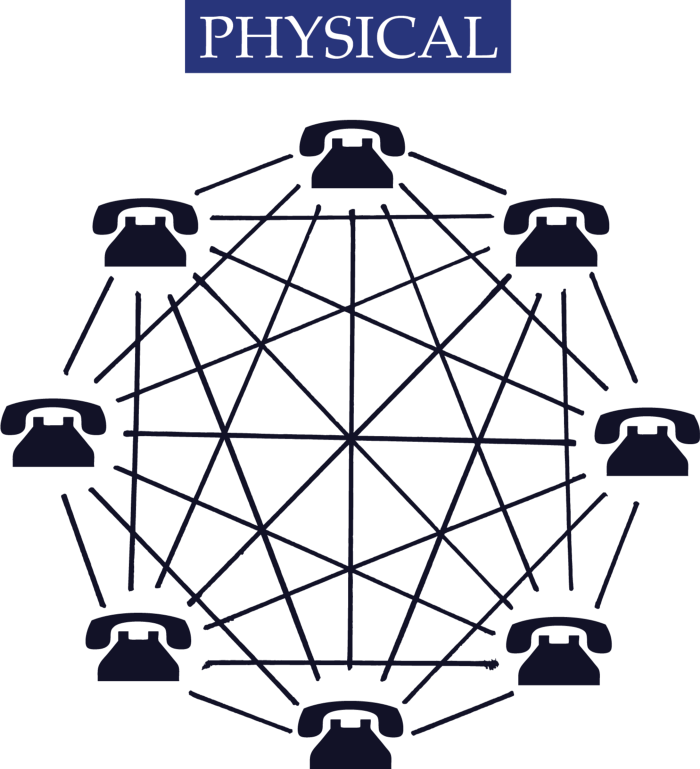

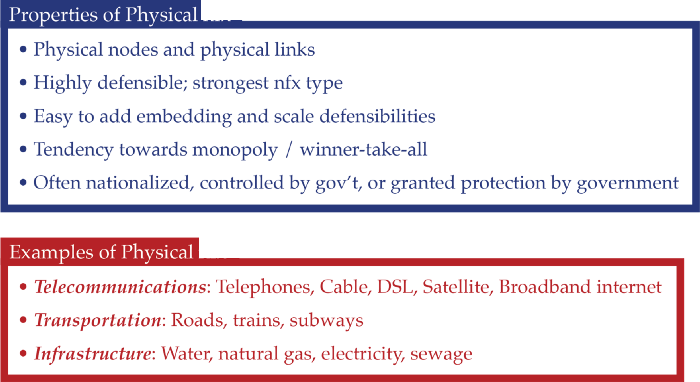

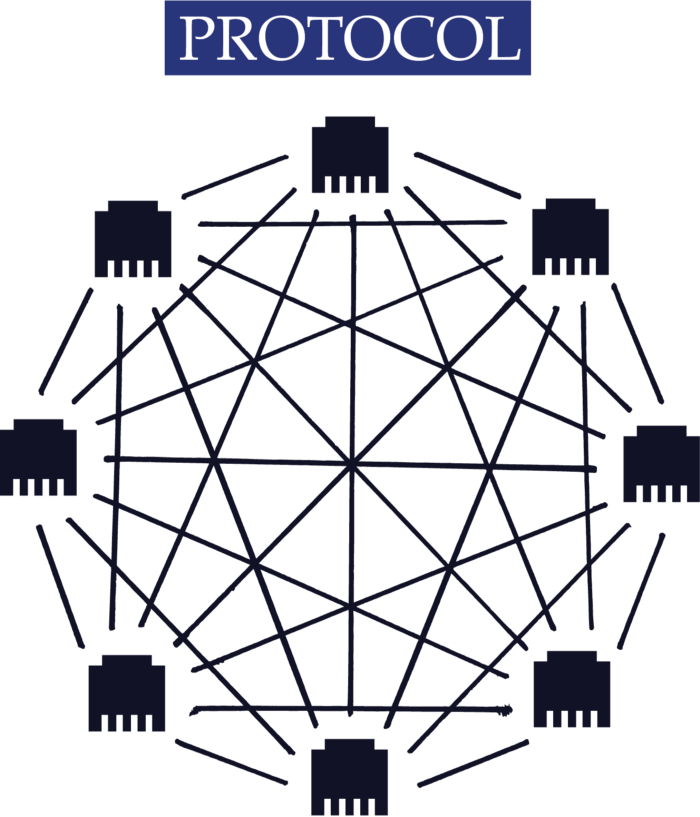

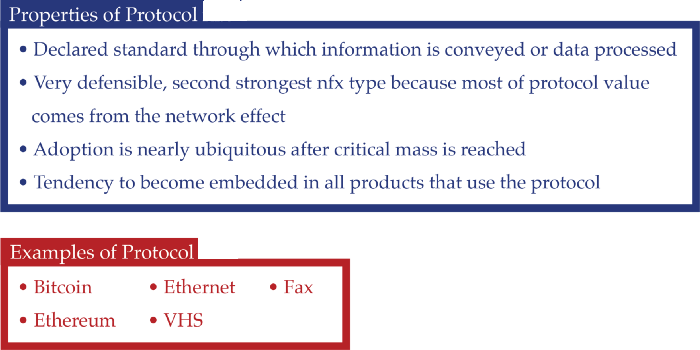

There are various ways to classify network effects. At a high-level, there are five major types of network effects.

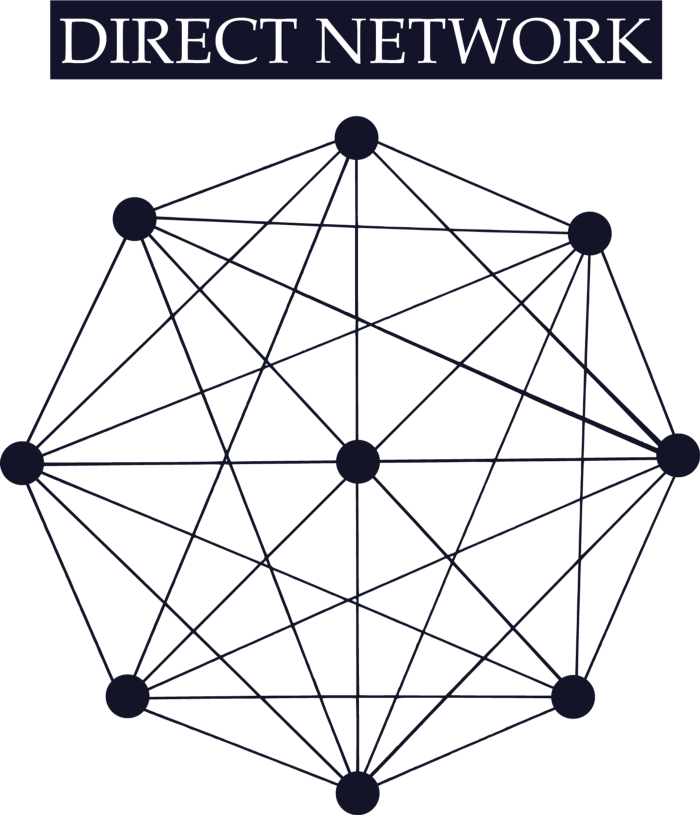

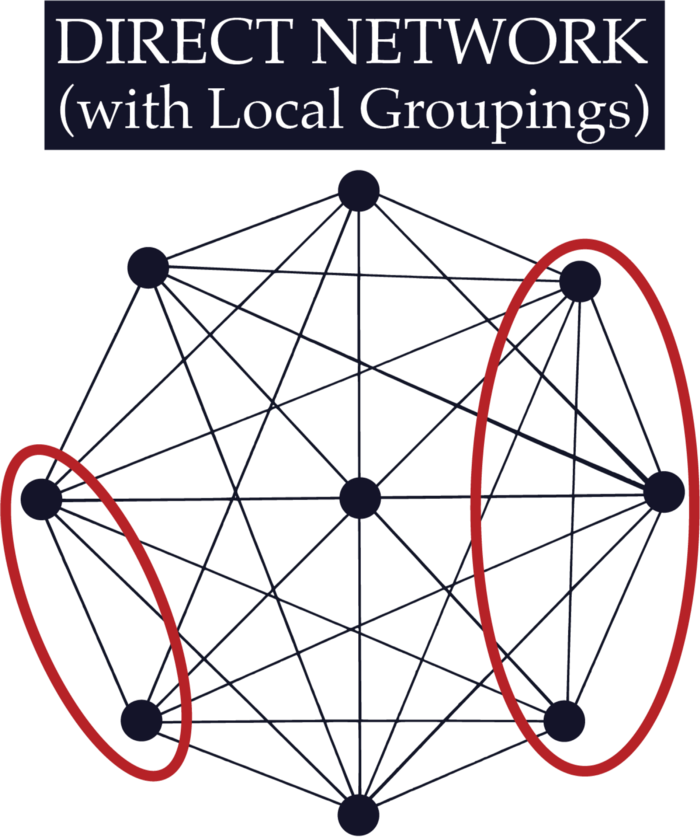

1. Direct Network Effect

The strongest and simplest network effects are direct: increased usage of a product leads to a direct increase in the value of that product to its users.

LinkedIn, WhatsApp and Facebook demonstrate this type of network effect. Once you have friends on Facebook or WhatsApp, you wouldn’t join other services. A new entrant has to achieve significant network effect in order to create values for users.

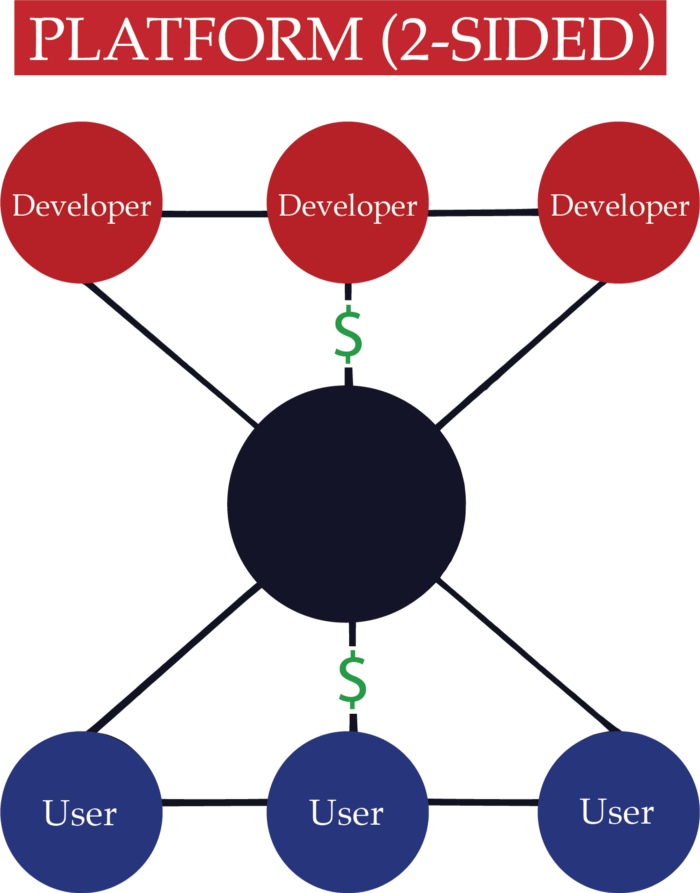

2. Two-sided Network Effect

The real distinguishing characteristic of a 2-sided network is that there are two different classes of users: supply-side and demand-side users. They each come to the network for different reasons, and they produce complementary value for the other side.

Marketplace and platform are two-sided network effect. This type of network effect is seen in Airbnb and Uber. When more drivers join Uber, it creates value for riders by reducing wait time for riders. Thus, more riders join Uber and rider demand creates value for drivers.

3. Data Network Effect

When a product’s value increases with more data, and when additional usage of that product yields data, then you have a Data Network Effect. If data is really central to the way the product benefits users, then the data network effects of that product has the potential to be very powerful.

Examples for this type of network effects are Waze and Google Maps. Waze users consumes data as well as contributes useful data to the network. Users’ data contribute to determine traffic and Waze provides optimal route to the users. So, if network is larger, Waze can provide more accurate data on traffic to the users.

4. Tech Performance Network Effect

When the technical performance of a product directly improves with increased numbers of users, it has Tech Performance nfx. For networks with Tech Performance network effect, the more devices or users on a network, the better the underlying technology works. This makes the product faster, cheaper or easier.

Every person downloading a file from BitTorrent is also seeding files to the network. So, the services get faster for all users as more nodes are on the network.

5. Social Network Effect

Social network effect work through psychology and the interactions between people. There is an unseen network among people, where our physical bodies are the nodes, and our words and behaviors with each other are the connections.

Social network effect can add value to people in three different ways:

- Language — brand name that people will verbalize (Uber, Google).

- Belief — the more people believe in value of something, the more valuable it gets in reality (Bitcoin).

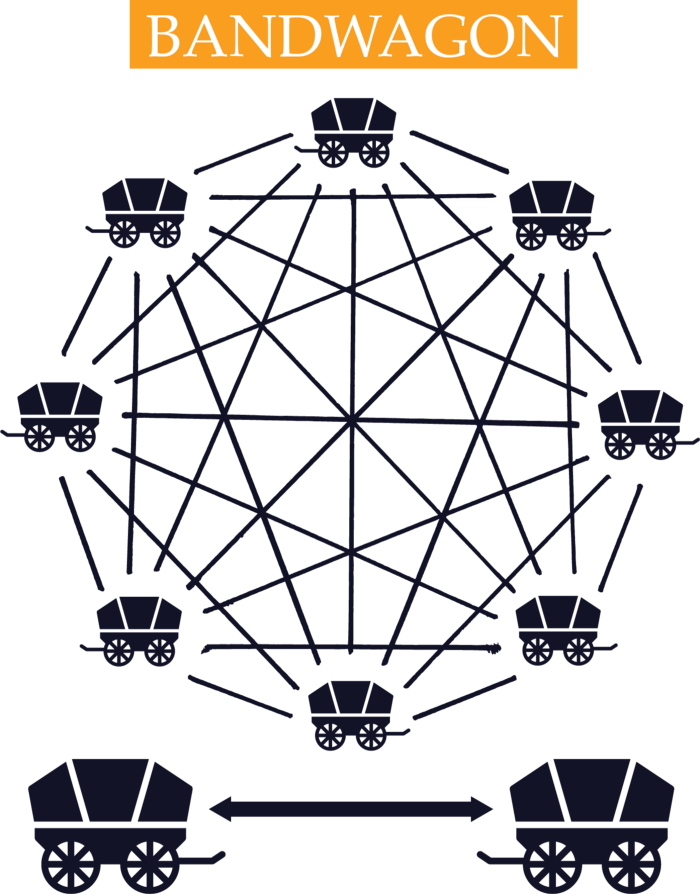

- Bandwagon — when social pressure to join a network causes people to feel they don’t want to be left out (Slack, Apple).

Why Network Effects are Important

In digital world, there are four ways to create defensibility:

- Supply-Side Economies of Scale,

- Brand,

- Embedding and

- Network effects. Network effects is the most important way to achieve defensibility. Companies with the strongest types of network effects built into their business model can achieve scalable growth and win big.

- Network effects is one of the most important strategies to achieve organic growth. Companies can grow from paid acquisition, but customer acquisition cost (CAC) would be too high and as markets saturate, CAC would rise and make it difficult to achieve profitability in long run. However, this is not true with network effects. As networks grow, all participants benefit and create value for other users which attract more users to use product. Thus, CAC remains constant or decreases over time and helps business grow organically.

- For example, Dropbox employed paid campaigns to acquire new customers during its initial days. Due to this, customer acquisition cost (CAC) was very high ~$300, compared to yearly revenue ~ $120 (~ $10/month). Clearly, it wasn’t sustainable for Dropbox to achieve organic growth with this model. Dropbox employed growth hacking tactic such as double referral program to boost user base. Once users started using Dropbox and shared a folder with other people to collaborate, it created a link that other people could use. This created an eco-system where new users started using the service because their friends shared a file with them. Furthermore, it led to a barrier to switch to a different file-sharing system and helped Dropbox to acquire new customers. Thus, an existing users hooked new users to use Dropbox. In other words, Dropbox achieved network effect which helped them to achieve growth and reduce CAC.

How Network Effect Works

- Network effect becomes significant after only when certain number of users are using the product. This certain number is called critical mass. The challenge lies in getting users to join in before the critical mass is achieved. In order to achieve critical mass, companies could offer services for free for a limited time and adopt various growth hacking tactics, such as referral bonus (as mentioned earlier in Dropbox’s case), request a friend to sign up or subsidizing fees for service.

- Once this critical mass has been achieved, the value obtained from the product or service is greater than or equal to the cost for the product or service. As the value increases by the number of users of a product, more users would want to subscribe/purchase the product, and hence more users would be added to that product, which would further increase value of product and make more people to join it.

- The above graph, depicts concept of network effects. It shows that once product achieves network effects, value Increases exponentially while cost increases linearly. The cost of maintaining the network does not grow as fast as the value of the network. The value increases as the size of the network increases. In the long run, it’ll be difficult for competitors to enter in the market as existing players would have more valuable network. So, there will tend to be fewer players, and they will continue to grow larger.

- For example, one of the most valuable aspects of the Spotify platform is music discovery. Listeners want to explore different genres of music and listen music beyond top playlists, while artists/record labels want their music to be reached to more customers.

- As more record labels/artists join Spotify, more users tend to join Spotify due to more music choices available on the platform, which in turn attracts more artists/record labels and collectively increases value of Spotify’s network. Also, Spotify users can see their friends’ playlist and recent activity. So, once you have more friends on Spotify, it creates stickiness of the product. The platform therefore ultimately becomes more valuable to users as more users join. Spotify curates and creates its own playlists, but much of the value comes from other users’ tastes. As more music listeners, bloggers, organizations get on Spotify, the more valuable it becomes to a listener as they have more curated music. Simultaneously, the more users on Spotify, the better it is for artists (increased streaming royalties and exposure).

- The more playlists, the more users, the better the music — discovery. Once Spotify has more users and artist on its network, in other words network effect is achieved, it’s really difficult for users and playlist to switch to other service.

- Considering network effects as a foundation, RIL JIO explores different types of network effects and various business models enabled by them to create never before realized valuations.

The Study

- We wanted to put an actual number on the amount of value network effects have created in the digital world.

- The short answer: over the past 23 years, network effects have accounted for approximately 70% of the value creation in tech.

- We did a study of the digital companies that were founded since the Internet was widely available in 1994 and that went on to become worth more than a $1 billion.

- 336 companies between 1994 and 2019 met this criteria.

- By looking at each of the companies’ business models and comparing them to our list of 13 known network effects, we estimate 35 percent of those companies had network effects at their core. They were, however, typically much more valuable than companies without network effects so they added up to 68% of the total value in our spreadsheet.

- In other words, companies that leverage network effects have asymmetric upside. They punch above their weight. They are the Davids that beat the Goliaths, and then become the Goliaths.

- The other 65% of $1B+ companies used other defensibilities to create their value — namely embedding, scale and brand. These are good approaches, and created 219 $1B+ companies. 65% of the total. But those companies’ valuations typically top out in the $1-$2B range, leading to the results of this study.

The Single Most Important Predictor of Tech Value

- It turns out that having a network effect is the single most predictable attribute of the highest value technology companies — other than perhaps “having a great CEO.”

- And yet surprisingly, only 20 percent of the business plans we came across had network effects in them.

- We believe that most founders fail to design network effects into their businesses because they don’t understand them well enough. And not understanding them, they don’t build them in from the beginning.

- It’s sad to watch, because just as the Big Five are now consolidating their dominant threat to startups, and just as startups have lost the favorable winds of the Internet and mobile tech shifts, most founders are missing a key ingredient they will need to have a dog in the fight.

- Unless founders wise up to the importance and discipline of network effects, the scales will be heavily tipped in favor of those who have.

- If Your Startup Doesn’t Have Network Effects, You Need to Rethink Your Strategy.

- There still remains a huge gap between how little is written and known about network effects and how massive of an impact they have on value creation (to say nothing of their impacts on society and the future of our economics and politics, but that’s a different discussion).

Network Effects and the Next Big Thing

- Some have asked, “The top companies of 2019 have network effects, but many of those companies were founded 5–20 years ago…will the power of network effects continue with new startups?”

- Unequivocally, yes.

- In fact, network effects will increase in importance because the new platforms — and the re-invented verticals — are being born networked:

– Crypto-Assets

– Synthetic

– Biology

– Augmented Reality

– Artificial Intelligence

– Virtual Reality

– Internet of Things

– Robotics

– Drones

– Transportation

– Smart Cities

– Agriculture

– Health Care

– FinTech

- Understanding the principles of network effects and applying them to new companies today should produce the same or greater defensibility and value-creation advantages that we saw in post-1994 companies, particularly because there are now over 3B people networked to the Internet. If we have to design an AI company with or without network effects, we’ll take the one with network effects every time.

Learn the Network Effects Playbooks

- When you’re creating your digital business, architect your product to allow users to participate in value creation. Let their use of the product add value to the other users. Let customer 2 add value to customer 1. This makes the company defensible because competitors have a hard time adding as much value to users once you get ahead, and defensibility creates value.

- If history tells us anything, the next SnapChat, Airbnb, and Uber will be created in the next twenty-four months. While the next billion dollar startup won’t look just like those companies on the outside, it’s a good bet that they will have network effects on the inside.

The Rise of the 4th Platform: Pervasive Community, Data, Devices, and Intelligence

- These days it’s still pretty common to talk about social business, mobility, analytics (especially when it’s called big data), cloud, and the Internet of Things — SMACT is the current acronym for all this — as on the agenda of key digital improvements underway in the typical enterprise.

- While many organizations have executed solid starts against these fronts, and are usually just at the end of the beginning overall in incorporating these technologies into their business, the majority still have a good way to go away.

- What’s coming next in digital and the enterprise. While examining the more strategic up-and-coming technologies for the last year, this doesn’t really begin to paint the strategic picture that organizations must manage to now.

- After all, a laundry list of technologies is just that, and won’t create results by itself. But carefully situating emerging technologies within a business in a way that truly takes advantage of their innate and unique abilities to realize value creation does, and is the essential description of the hot topic today among CIOs and others in the C-Suite, digital transformation.

- After all, the whole point of digital transformation is realizing that technology fundamentally changes how you do business in just about every way. It therefore poses very difficult questions to business and technology leaders: Who best should do our work today? Where does the value come from? What do these new ways of working actually look like? How can we best organize to achieve them? To answer these questions, we must understand the overall narrative of our modern digital journey: Where is technology actually taking us? What is it making possible that wasn’t before? How can these possibilities give rise to uniquely valuable new types of assets that would allow us to sustain our businesses?

- These are a lot of open questions, but we do have a sense of some of the answers now. For example, in terms of who does the work and where value comes from, we’ve learned that the network can and will (and should) do most of it, if we only enable the possibilities through platforms and digital communities. The answers to other questions are more complex, though their broad outlines are becoming clear as well, such as how can we best organize this year to achieve digital change. Why are they tough questions? Because while digital devices and networks enable broad and reasonably well-understood realms of possibility, how precisely they apply to our industry, our business, and our corporate culture is often very different between organizations.

- So when we talk about framing up the overall digital journey we are all on, the discussion is often about “computing eras”, or the emerging of new types of platforms (the cloud, for instance.) while these views are often gross simplifications, these are also useful conceptual frame-ups. Probably one of the most widely referenced view these days is IDC’s articulation of a vision they’ve dubbed the 3rd platform. In the large, this view does indeed describe what’s happening, though it leaves out some of the unique flavor of what’s special about what’s happening in digital today. We’ve previously described some of the more detailed possibilities in a view called Web OS, but this really never became a popular way of thinking about it, though it did provide the extra layer of detail many need to understand what’s happening and has held up well in my opinion.

What’s Missing, and What’s Coming for Today’s Strategic Digital Perspectives?

- Probably the most important concept that’s almost always missing from these views is the unique power of networks, especially ones made of people. One of the more remarkable is the sheer number of connections between nodes on the network that are potentially possible. Old ways of thinking about digital created largely point-to-point connections. The advent of social media made potent many-to-many network effects possible. The key word here is possible. Just because we’re connected to just about everyone in the developed world 24 hours today, doesn’t mean we actually realize that possibility. But today’s global networked platforms gives rise to the potential. In fact, for many reasons, having the ability to tap live into one’s social network is often better than having data on-hand, which is likely to be out-of-date.

- So, for example, our view of what’s coming next, we don’t track the amount of data that is accumulating today. That is a great deal and growing rapidly by every account. But data isn’t useful until it’s needed, instead the ability to produce whatever is needed, when it is in fact needed, has far more ultimate value. So in our view, it’s key to understanding the strategic business nature of digital networks. This is a key point that summarizes excellent Power of Platforms series:

But in a world of mounting performance pressure, we should also expect a fourth form of platform to become prominent. Dynamic and demanding environments favor those who are able to learn best and fastest. Business leaders who understand this will likely increasingly seek out platforms that not only make work lighter for their participants, but also grow their knowledge, accelerate performance improvement, and hone their capabilities in the process.

- The core concept here is that whoever learns fastest, wins, and those with the best platform and ecosystem around it, will have value that can be tapped into more rapidly for sustained strategic benefit. Plus, it will ensure coverage of virtually all of the top level types of collaboration in business today.

What’s Next: Networks/Sensors In Everything, Machine Learning, and Us

- Just about every non-trivial object will be connected to our networks within 10 years, as part of the rapidly emerging Internet of Things revolution. With the introduction of low power protocols like Bluetooth 4 and ultra long-lived batteries in devices like the tiny — and terrific in experience — Tile locator, we now believe it’s going to be more like five years.

- It’s also clear that mobility is going to transform and essentially disappear, into us. Wearables and smartphones will very quickly quaint when everything we need can be beamed into our heads or embedded as needed. Computing devices will almost completely disappear into our personal and work objects, and even ourselves. While this is certainly as scary a topic as the loss of privacy on the Internet was to many of us a decade ago, it’s clear that our computing devices are going to vanish and melt into the backdrop, like any sufficient mature technology. In fact, almost every technology eventually becomes naturalized. This will be the case with the end-state of digital experiences as direct man/machine interfaces, which have long been in the lab and is becoming increasingly sophisticated en route to the market.

- Thus it won’t be long from now — as strange as it may seem today — that we can turn on the lights in our office just by thinking about it or order a product from Amazon after having an algorithm sift through the reviews for us simply by conceiving of doing so. We will reach a state of shared perception through all of our mutually connected devices and having knowledge networks consisting of our social graph, all devices, and the machine learning capabilities we trust most. In other words, collaboration with people and our machines will soon be truly frictionless.

The Fourth Platform: Ambient, Pervasive, AI-Boosted Digital Networks

- All of this together: Networks of people in digital communities, pervasive sensors/controllers in nearly everything, and new types of truly frictionless interfaces will give rise to new types of ecosystems, including on-demand app creation services such as the now-famous IFTTT service.

- The 3rd platforms enabled enormous commercial ecosystems such as those created by Google (especially their decentralized AdWords network), Facebook, Amazon’s Cloud, Apple’s phones, iTunes and App Stores, and the list goes on. In the 4th platform, these platforms will become even more important — rightly or wrongly — and the most useful ones to us will literally become part of our mental furniture.

- The fourth platform is ambient computing, which strong components that turn network potential from our favorite ecosystems into data, and then data into knowledge, and make it as easy as just thinking about it. The next generation commercial ecosystems will even augment time and thought for us, even predicting what we’ll need before we figure it out ourselves.

- If all of this sounds a little futuristic, it is also now all just within the realm of possibility, and so it will almost certainly happen, it’s just matter of exactly when. It also gives our organizations a clearer target to shoot for, at least if your organization considers moon shots. Because most organizations are struggling with being a digital contemporary in basic terms, much less getting ahead of the game. But there are ways of getting there, if organizations are prepared, it just takes a vision of the future to aim for.

- We will explore more about the fourth platform soon, but would love to hear your thoughts on how networks, people, and devices are coming together to create all new possibilities for the enterprises.

CyberPhysicality — Defining a Digital Twin Platform

- Digital Twin is considered one of the key trends for IoT. The idea of a digital twin is to create a digital replica of a physical object and use the twin as the main point of digital interaction. A digital twin could be a factory lathe, a windmill, a container ship, or automobile. Gartner Group has listed digital twins as one of their top 10 technology trends. A survey conducted by Gartner found close to half of organizations are using or plan to use digital twins in 2018.

- A lot of has been written about digital twins, especially about the concept and benefits. There are lots of very cool demos/videos that showcase digital twins in simulations and VR/AR scenarios.

- What is less clear is the technology required to build and deploy digital twins. What technology is needed for organizations to make digital twins a reality for large-scale deployments. How do you manage thousands of digital twins or thousands of different types of digital twins? How do you integrate a digital twins with other systems?

- For organizations that want to scale out a digital twin strategy, we believe they are going to require something like a digital twin platform. However, the question becomes what defines a digital twin platform? It seems there are 6 key features that would define any scalable digital twin platform.

- Manage the Digital Twin Lifecycle — How do you design, build, test, deploy and maintain a digital twin and its digital master? Digital twins are the instantiations of something called the digital thread or digital master. For instance, each windmill will be based on a common digital master that represent the engineering diagrams, bill of material, software versions and other artifacts used to create each windmill. A digital twin platform needs the tools to bring all this information together to create the digital master and then manage any changes to the digital master. Tools then need to be available to test, deploy and manage each digital twin based on a specific digital master. The tools also need to be able to handle hundreds of digital masters and thousands of digital twins.

- Single Source of Truth — A digital twin is suppose to be an exact replica of a physical asset and the data coming from the asset. However, the maintenance of a physical asset can often change its physical state. For instance, a specific windmill might have a replacement part or a different version of firmware installed; other windmills might not have the same updates. A digital twin platform is able to update and provide the exact state for each individual digital twin, creating a single source of truth.

- Open API — A well defined digital twin becomes the interface and integration point for an Industrial IoT solution. A digital twin platform provides an open api that allows any system to interact with the digital twin. For instance, machine learning and analytics services should be able to interact with a digital twin through an API. An organization should be able to integrate their digital twin into other enterprise systems, like ERP or SCM systems. A digital twin API should really enable the concept of Device as a Service.

- Visualization and Analysis — Organizations should be able to use their digital twin platform to create visualizations, dashboards, and in-depth analysis of this live data from the digital twin. The live data should be linked to the digital master to allow for drill-downs into design documents or other components of the digital master.

- Event and process management — It should be possible to setup events and business processed to be executed based on digital twin data. For instance, events to schedule maintenance calls based on live data and an accurate view of the current maintenance status of the physical asset.

- Customer and User Perspective — A digital twin platform needs to provide a customer and user perspective. What organization own or operate each digital twin? What users are allowed to access the data and information associated with the digital twin. How can you share information with other users that might be involved in the design of a new release for the asset. A digital twin platform needs to enable collaboration between the stakeholders of the digital twin.

4 Th Platform

- Platform business models are fast becoming the golden child of the digital revolution. As digital platforms disrupt and dominate markets to create communities of enormous scale, they deliver compelling customer experiences and offer new forms of innovation and value creation. Yet, most new platform businesses will fail unless players acquire a new mindset and business approach.

Platforms are pervasive

- Until recently, digital platforms were the preserve

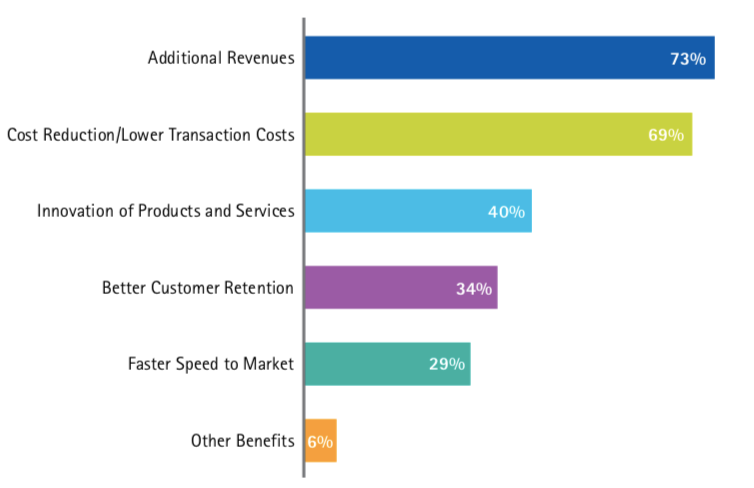

of technology and digital-born companies, such as Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon, and of digital start-ups, such as Airbnb and Uber, that are fueling the on-demand or sharing economy. Now, resourceful entrepreneurs acting as digital partners — app developers, complementors or affiliate providers — can reap rewards from the platform economy. They can generate revenue, reduce costs, innovate products and services, or gain speed to market. And, as this report shows, they can do it anywhere. - Traditional incumbents, too, are developing their own platforms, working with innovative entrepreneurs and undertaking alliances or acquiring companies. For example, Philips is reinventing itself in the fast- emerging health technology market in this way. Research suggests platforms’ total market value is US$4.3 trillion, with an employment base of at least 1.3 million direct employees and several million indirectly employed at partner companies that service or complement platforms.

Platform Success Relies on Five Steps

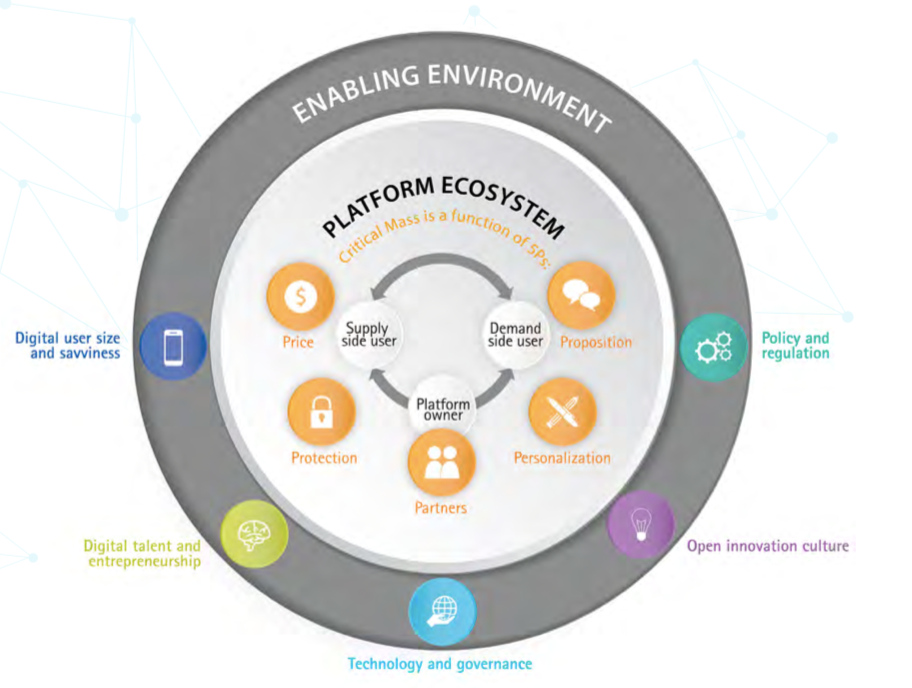

- Five factors that generate the network effects and critical mass crucial to the success of platform ecosystems (proposition, personalization, price, protection and partners) and highlight the five underlying environmental enablers that are necessary for platforms to flourish (digital user size and savviness, digital talent and entrepreneurship, technology and governance, open innovation culture and policy and regulation).

- In assessing the digitalization maturity of several countries, it is found that not all countries provide an environment that is conducive to platform success. Platform Readiness Index shows that the United States, China, the United Kingdom, India and Germany top the rankings of those countries with the biggest opportunity to grow and scale digital platforms — and will retain their top five ranking in 2020. Countries such as Italy, South Africa and Russia are currently at the bottom of the table and must rapidly introduce ambitious policies if they are to boost digital platforms and narrow the gap with leading countries by 2020.

The pervasive power of platforms

- Digital platforms are transforming market competition in all industries around the world and platform-based companies are gaining market share rapidly. Entrepreneurs are ideally placed to play a variety of roles in the platform economy as a means to accelerate their own growth.

- Although traditional incumbents have started to react, less than

15 percent of Fortune 100 companies have a developed platform

model today. But the trend toward platform adoption is expected

to continue — IDC predicts that, by 2021, more than 50 percent of

large enterprises will create or partner with industry platforms. The platform revolution that began in the business-to-consumer (B2C) area through eCommerce, FinTech and circular economy business models, is expanding into the business-to-business (B2B) space with innovation- based ecosystems and data-enabled business models, such as the industrial Internet of Things (loT). This is mainly driven by companies shifting their focus from selling products to offering outcome-based services through digital platforms. - The concept behind platforms is not new. Shopping malls link consumers with merchants, and newspapers have connected subscribers and advertisers for more than a century. Now, the availability and convergence of affordable digital technologies is enabling companies

of all sizes to embrace mobile and data and analytics while adopting

a “cloud first” approach to redesign their business models. One of the advantages of digital platforms is their ability to introduce a new “pay- as-you-go” business model that enables efficient, low-cost speed to scale and the creation of new, richer customer experiences.

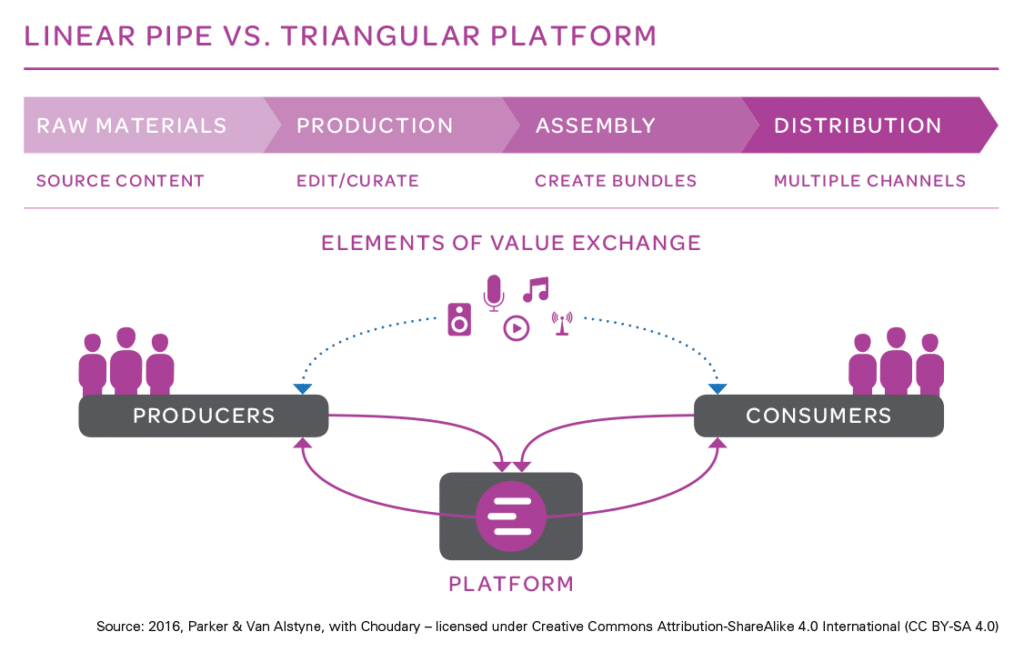

What is a digital platform?

- A digital platform is a technology-enabled business model that creates value by facilitating exchanges between two or more interdependent groups. Most commonly, platforms bring together end users and producers to transact with each other. They also enable companies to share information to enhance collaboration or the innovation of new products and services. The platform’s ecosystem connects two or more sides, creating powerful network effects whereby the value increases as more members participate.

- Platforms’ development can be accelerated by third parties’ provision of application programming interfaces (APIs) that enable participants to share data to create new services. Thanks to cloud and other technologies, they can provide resources on an as-a-service basis. Successful platforms operate under clear governance conditions that protect intellectual property and data ownership, fostering trust among participants.

Three sources of discrete power

- The power behind digital platforms lies with three distinct features. First, the network effect of bringing together market participants means that more customers attract a greater number of merchants and partners, and vice versa. This shifts the cost and risk burden of creating markets from the business to the network. As the network gathers its own dynamic momentum, the platform owner acts as a facilitator to spread that burden among a growing number of participants.

- Second, the concurrence of technologies — cloud, automation, analytics, artificial intelligence, mobile and the industrial internet — is creating

a new “as-a-service” economy, where services are dynamic, on-demand and targeted, and have a huge impact on cost to serve, investment levels and speed to market. By integrating business processes, software and infrastructure and making them available “on demand,” large and small companies can benefit from plug-in, modular, scalable services. Entrepreneurs are particular beneficiaries here; without the constraints of funding the full costs of a platform business up front, they have access to new markets and distribution channels. - Finally, open and shared data can be mined intelligently by specialists, including those from adjacent industries, to create new forms of value. Insights might be generated from monitoring customer behavior at scale or from products or machines being used in the field. Indeed, huge volumes of data are being generated today and are estimated to double every two years to 2020. This new, collaborative and agile way of working is catching manyorganizations off-balance.

- While it used to take Fortune 500 companies an average

of 20 years to reach a billion-dollar valuation, today’s digital start-ups can get there in four years. Digital platforms are largely responsible for this shift.

Platform opportunities for all enterprises

Platforms open up the potential for entrepreneurs and small businesses to generate demand-side economies of scale that would be otherwise far beyond their reach. More specifically, they can play an active role in the platform economy as:

- Platform owners: design and develop the platform, control intellectual property and decide how it will be run. Owners also manage users and partners who can add value to the core platform offering. For instance, Germany’s Fidor Bank, recently acquired by French banking group BPCE, solicits the participation of community users and partners to enable both traditional lending and lending via peer-to-peer capabilities.

- Digital partners: team with platform owners to offer complementary products and services using application programing interfaces (APIs). For example, Fidor Bank maintains a close alliance with global payments provider, Currency Cloud, and extends multi-currency payment services through API integration with the provider.

- Producers or suppliers: act as merchants selling goods directly to consumers or to businesses in the marketplace. For example, individuals in the Fidor banking community supply credit to their community peers that are in need of finance.

- To succeed, entrepreneurs must determine whether they will act as platform owners, digital partners or suppliers. Entrepreneurs acting as platform owners need to consider a host of market factors and individual capabilities before deciding to launch their platform. One of the primary considerations is whether markets are contestable or if the barriers to entry and sunk costs are too high. In China, for instance, all new contenders to the search engine space have failed within three years as Baidu continues to hold a formidable market share.

- Yet, newcomers with a compelling value proposition have forged their own success and disrupted markets previously dominated by incumbents. The opportunity is undeniable; business avenues that were previously beyond the reach of entrepreneurs are now accessible. The United Kingdom’s Venture Founders is a platform owner that has opened up early-stage investments to a wider base of savvy investors — previously reserved for the likes of private equity, venture capital and angel networks.

- Entrepreneurs acting as digital partners can help platform owners achieve scale by offering complementary products, growing alongside platform owners as a result. For example, Canada’s Shopify, which provides cloud- based commerce solutions, expanded to about 150 countries within a decade of being set up. Entrepreneurs also benefit from the technical, financial and mentoring support of platform owners. For example, the United Kingdom’s Swave start-up is developing a consumer financial literacy app and benefits from its access to Lloyds Bank’s digital experts and data for building the product. Entrepreneurs will need to adapt their business models to offer services “on demand” — for instance, accounting as a service. Further, platform owners seek to engage in an end-to-end collaboration in which the digital partner assumes some responsibility for the success of initiatives and accepts compensation based on the outcomes it commits to deliver.

- Entrepreneurs acting as suppliers on a platform have access to a new distribution channel and benefit from additional revenue and reduced transaction costs, among others. In particular, eCommerce platforms facilitate suppliers’ participation in global value chains due to improved access to market information and marketing skills.

- Participating in platforms is not without risk and requires entrepreneurs in all roles to reassess their strategies, capabilities and resources. Small companies and entrepreneurs need to rethink traditional product-driven approaches to become more customer experience-driven. Complexities arise around monopolies and competition, ownership and intellectual property rights. Open architectures and data sharing place an even greater emphasis on managing data privacy and security for customer data collection and usage. Finally, platform success often depends on the ability to form partnerships with players, often in adjacent fields, to create and deliver new customer experiences. Platform business models require continuous adaptation and agility to maintain the equilibrium of the two-sided market, which in turn generates positive network effects.

- Ultimately, entrepreneurs must plan for the long term and acquire the critical mass and scale that is integral to platform success. Smaller players can survive or resist being acquired when operating with a strong, niche offering, but the ability to access growth capital and scale fast still lies at the heart of platform success.

A winning formula

Two essential dimensions must be mastered to develop a successful digital platform business

- Create a dynamic platform ecosystem that enables businesses to achieve critical mass:Critical mass is dependent on mastering five distinctive capabilities that we call the five Ps: a differentiated value proposition, service personalization, market responsive pricing, effective cyber protection, alongside taking advantage of the scalability power of ecosystem partners.

-

Foster a supportive enabling environment:

There are factors and conditions within the broader economy that are required for platforms to emerge and grow — digital user size and savviness, digital talent and entrepreneurship, technology and governance, open innovation culture and public policies.

Create a dynamic platform ecosystem — Five ways to win

- Competition in the platform economy will be fierce, especially as companies from adjacent sectors extend beyond their traditional markets. Yet, although there is no “one-size-fits-all” platform model, we have identified five ways a dynamic ecosystem can drive platform success.

- Platform failure is surprisingly hard to track. Fortune notes that nine out of 10 startups fail while CB Insights reports that more than 70 percent of all failed technology companies have been in the internet sector — and this percentage has been consistent over the last few years. On the failure list, online marketplaces rank second after social companies.

- Less than 10 percent of start-up platforms will succeed to become profitable independent entities — even lower in markets such as China where the platform market is highly competitive. For example, the vast number of online lending platforms in China alone was reported to be in the range of 1,500 to 1,700 in early 2015. It is questionable how feasible it will be for this number of peer-to-peer lending platforms to scale in a fragmented market that is further fractured by offline lending institutions.

- Barriers to entry are becoming higher. Large platform players are expanding geographically, shifting from business-to-consumer to business-to-business (examples include Airbnb, Booking.com, Expedia and Uber), or developing online-to-offline models that move them from digital channels to physical stores (like Amazon, DHgate or Paytm).

- Large companies will also be challenged to adapt their culture, practices and operations to suit the particular demands of customers and partners in the platform world.

- Adjacency between industries, sectors and countries will increase in the coming years, bringing more and more players into direct competition with each other. For instance, Google has expanded from search to maps, a mobile operating system and autonomous cars. In financial services, digital wallet products from Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon (“GAFA”) as well as Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent (“BAT”) have encroached on the territory of digital players like Paypal, as well as traditional banks.18 In India, Flipkart has added a mobile wallet to its eCommerce platform, and mobile payments service, Patym, has entered the digital commerce marketplace with a banking license and its own eCommerce service.

- The challenge does not end here. As the market has shown, the power of network effects can act in reverse and destroy value at explosive speed — companies can miscalculate one or more sides of the multisided marketplace or quickly lose their critical mass to a peer platform, such as Orkut’s closure in 2014 as social media enthusiasts shifted to Facebook.

Create a dynamic platform ecosystem: Five ways to win

- Attracting a critical mass of users — on both demand and supply sides — is important to create value at scale. Frequently, platform owners must emphasize critical mass over profit generation in the initial stages of platform development, while maintaining a focus on value creation. For example, Alibaba’s Taobao platform used free listings to gain user momentum. Although the platform began to charge once it achieved critical mass, sustained value has been achieved through the personalization of the user experience, a wide range of horizontal services and the protection of customers by addressing security and counterfeit issues.

- Critical mass is a function of proposition, personalization, price and protection, orchestrated by the owner with an ecosystem of partners. Each of these five Ps takes on new meaning as companies move from traditional “pipeline” businesses (that succeed by optimizing the activities in their value chains, most of which they own or control) to platform businesses (that bring together consumers and producers).

Proposition: Present a compelling solution through modularity

- Traditionally, proposition is about the value produced by companies and sold to consumers, but in the platform world it is about users creating value for other users, facilitated by the owner. A platform requires continuous innovation in terms of value proposition and business model to create superior value for users, suppliers and partners in the ecosystem. For example, China-founded DHgate.com’s B2B proposition, “from factory to global customers,” is realized through a cross- border trading ecosystem — representing logistics, payments, internet financing, and technology innovation capabilities. Sellers benefit from increased margins with no middlemen, a shorter business cycle and extended global reach, along with strong local language services. Buyers enjoy a seamless and secure bulk purchase experience, supported by sellers’ customer service representatives trained by DHgate. The use of APIs is critical to market proposition, enabling a modular approach to platform development and revenue growth. For instance, Salesforce reportedly generates 50 percent of its revenues through APIs, eBay nearly 60 percent and Expedia a substantial 90 percent.22

Personalization: Center on the user journey

- From a customer point of view, the driving force behind platforms is the personalization of an experience that is less oriented around products, as in the traditional business world, and more around the outcomes. Targeting individuals and organizations through tailored experiences across all channels at scale relies on mass personalization. The aim is to understand customer intent and then dynamically and uniquely tailor experiences to each customer and context in a seamless manner across channels. For example, Amazon uses “interest and intent collection management tools” to encourage buyers’ “stickiness” (see “Data-driven personalization at Amazon”). The platform’s ability to use customer data to personalize interactions will vary by country and even region based on data privacy laws.

Data-driven personalization at Amazon

- The success of Amazon is data driven and its use of customer data to predict market needs and optimize business operations helps it to maintain market leadership. The company draws on predictive analytics to power recommendations that help it upsell. Service features, such as #AmazonWishList, enable customers to tailor buying lists that create stickiness, drive engagement and improve buyer retention. Predicting purchases based on behavioral patterns of a customer’s previous transactions on Amazon is also set to create a more personalized approach. A patent for anticipatory shipping will take data about a customer’s browsing and buying habits on the site, alongside real-world information such as telephone inquiries, to ship goods before a customer has even made the decision to buy. The combination of voice control and artificial intelligence offers a further opportunity for the hyper-personalization of the shopping experience. Amazon’s Echo devices, with the built-in voice- enabled Alexa platform, enable customers to order anywhere, anytime, while providing Amazon valuable insights on user behaviors.

Price: Engage participants through sophisticated, dynamic pricing

- Where traditional business pricing policies merely aim to recover charges from customers, pricing strategies can differentiate platforms by presenting opportunities for greater flexibility and reward. A freemium approach means users have easy, generally free, access to a platform before deciding whether they want to be buyers. Alternatively, pay-as-you-go pricing can be combined with fixed subscription fees. Surge pricing is increasingly used to manage peak demand, in contrast with discount pricing in periods of low demand. For example, Airbnb has rolled out a smart pricing system for all hosts on its platform that adjusts room prices based on changes in demand in real time. A platform’s flexibility with surge pricing will depend on local rules, such as the legal directive for Uber and others not to charge beyond government-prescribed rates in India.25 More generally, pricing on platforms depends on price elasticities on the demand side versus the supply side: the side with the greater elasticity often ends up being “subsidized” by the other side, at least during the period of initial launch of the platform. Scale can transform pricing strategies. China’s Alipay offers online payment rates that are a fraction of local and global peers, being on average 0.6 percent compared to Paypal’s 2.9 percent. But the company is profitable due to a user base that is two and half times the size of Paypal’s and payment volumes that are seven times higher than its American peer. Data monetization remains one of the most promising opportunities of platforms

Protection: Embed trust at the heart of the platform

- Cyber security is key — customers need to be sure the right safeguards are in place. Authentication of community members and their activities is the primary responsibility of the platform owner and partners, far more than in an offline business where physical verification is fundamental. Protecting a platform needs to account for both prevention and compensation. Handled correctly, platform owners can differentiate themselves with their commitment to protection. For instance, China’s DHgate.com, the B2B eCommerce platform, has announced 2016 as the “Year of Trust and Safety.” The company’s partnership with Authenticate it around product tracking, anti-counterfeit technology, upgrades to the merchant rating system and an escrow system, aims to build buyers’ confidence. Additionally, DHgate.com’s compensation measures include a collateral fund, buyer inconvenience reimbursement and penalties for fake shipping numbers.

Partners: Collaborate for scalable capability and agility

- The vital role of digital partners should not be underestimated — whether as product or service complementors, payment providers

or app developers — in helping to complete the platform offering and jointly fulfill customer needs. This contrasts a traditional company whose vendors are often detached from business outcomes. And partners can support platform owners to scale quickly. This is well illustrated in the open innovation that is behind many of the new FinTech companies’ approaches. For example, the modular design of U.S.-based Quicken means that large parts of the production chain are conducted by external providers, including sophisticated functions, such as predictive and specialized fraud analytics, and not only simple back-office activities.26 In its simplest form, collaboration may be a joint go-to-market approach, such as the referral partnerships of the UK’s NoviCap with TransferWise and Kantox on foreign exchange services for SMEs, and Sage on accounting software.

Data monetization — the quintessential competency

- Data generated by platforms proliferates — whether from analysis of user experience, behaviors, service consumption or productivity measures. In turn, this creates a multiplier loop, where the value of data multiplies with the number of users and partners in the ecosystem. Platforms enable the gathering of data and the generation of real-time insights on customers, market trends and operations. Indeed, the rich volumes of data and the speed of intelligent service enhancement that is feasible on platforms are possibly beyond reach of the traditional business model.

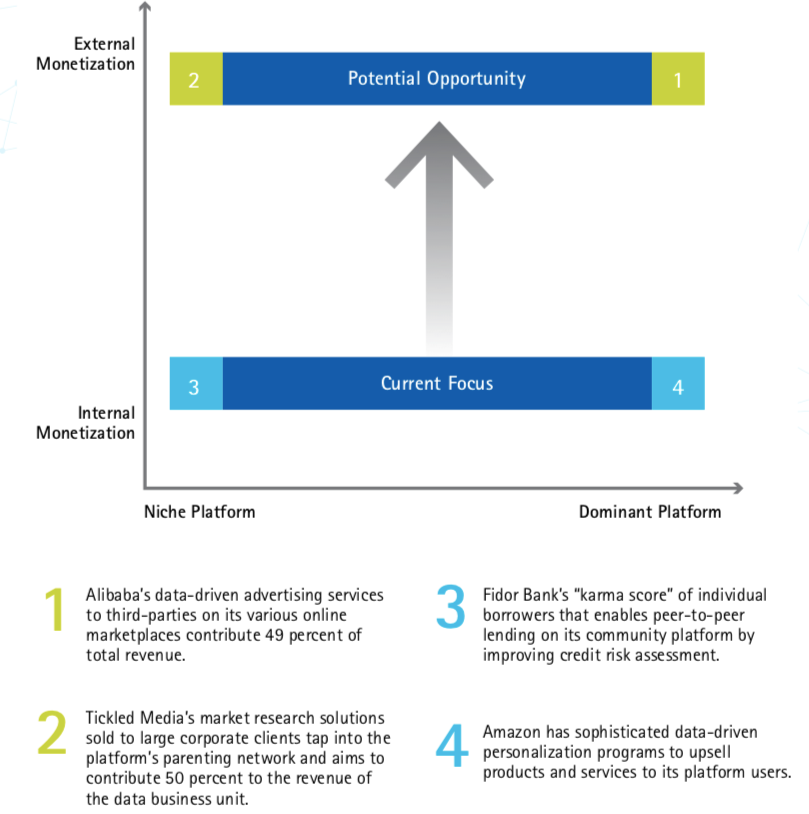

- The largest data-driven opportunity is the ability of a platform to capture value by creating new products and services, improving user experiences, managing risk and increasing productivity. These are avenues of internal monetization where data-driven enhancements are generated within the company. The impact is difficult to measure and the opportunity is often not maximized. Data monetization can also be achieved by providing data-based services to third-parties — which can be a high-margin business for platform players.

- Although the largest opportunity will be internal monetization, the potential for external monetization is high if the platform holds unique data and has the capability to package innovative services around that data for third parties. While some platforms are primarily transaction oriented and others are strongly data oriented, the opportunity from data monetization is undeniable for all platforms.

- The quality, uniqueness and richness of data are not the only determinants of internal and external monetization. Technology and workforces must have the capabilities to draw insights from the data. Platform players must adhere not only to privacy regulations, but also meet ever-increasing customer expectations around trust, privacy and security. Platform owners must safeguard usage and data rights, and ensure all participants conform to the local regulations for the jurisdictions in which the platform operates.

- Alibaba’s asset-light model means China’s biggest online eCommerce company can invest in next-generation technologies and services, such as cloud computing and big data, to maintain its competitive edge. Data — and better understanding of it — is integral to the company’s operations. More than 37 percent of Alibaba’s workforce is science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) talent, mainly employed in database management, machine learning and artificial intelligence.

The data insights gained are being monetized in a number of different ways. For instance, Alibaba uses data to derive 49 percent of its group revenue from advertising services, including third-party advertisers. “Super-ID” under the Dharma Sword initiative tracks the preferences of 630 million users, the vast majority of China’s internet population. Sellers pay a monthly fee for Alibaba software that they use to analyze relevant

data and personalize services for customers. Smart logistics

data predicts supply and demand and guides platform sellers

to pre-transfer merchandise to designated warehouses where there is strong demand. Finally, Alibaba is developing a unique enterprise credit system by bringing together data on sellers’ financial records, including affiliate Ant Financial’s records, past transactions and information from partners, such as banks. - Unique data can be of immense value to businesses and societies outside the platform business. For example, the Singapore- headquartered Tickled Media, a community platform for parents in Asia, has more than six million users across India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. The company created a separate unit called theAsianparent Insights that aims to drive one-half of its revenues from providing data on the niche segment, the parents, to large companies such as Nestlé, Pfizer, Unilever and others. The data business unit can create on-demand market research solutions faster than any consumer survey company can today by running surveys, competitions or testing products and marketing strategies among its extensive user network on behalf of corporate clients

How incumbent companies can succeed

- Traditional companies can successfully embrace platform-based business models if they align their operating model and culture, and work effectively with entrepreneurs in the platform environment. Company age is irrelevant when it comes to creating a platform business. Apple was more than 20 years old before it launched the iTunes and App Store platforms. General Electric was a century old when

it launched its software for the industrial internet, PredixTM. Incumbents are well positioned to make the best use of their current customer base, brand, market expertise and industry know-how when launching a digital platform. Yet, incumbents must be mindful of the specific demands of a platform business. - It is essential to identify early on which areas of the traditional business are prime for disruption and where the platform model can be a growth engine that generates network effects. For some, this means freeing themselves from traditional industry vertical boundaries; for instance, the Bosch ConnectedWorld of IoT-empowered solutions in energy, industry, transportation and buildings. For others, a vertical depth is integral to the strategy, such as the Philips HealthSuite digital platform that brings connected care for patients and providers.

- Each platform plan needs to be supported by new technology capabilities, especially APIs, and take account of their integration. This is where the partner ecosystem is critical to success. Other technology capabilities include mobile development platforms, the Internet of Things, infrastructure and cloud services, data-driven intelligent operations, rapid prototyping and testing capabilities, and real-time integration between the platform and the rest of the business. For example, Siemens MindSphere, a cloud platform for industry, collects and analyzes data that is created during production processes at industrial companies, as well as during the delivery of services. Based on this data, companies have new opportunities to further optimize their processes — and to develop new data-driven business models. Success of the platform is founded on Siemens helping its MindSphere corporate clients embrace new data capabilities, including the development of customer-specific business models and integration of different IT systems.

- Operating model transformation is also a necessity. Incumbents must design new open organization structures and processes. Using a dual operation model can address the tensions between legacy organizations and processes on the one hand and new infrastructure on the other, allowing the two to merge over time. Incumbents must attract and motivate talent — specifically from the developer community — and promote a creative culture. Governance of platform businesses is different than in traditional business, due to the way data

and transactions are shared between participants. Incumbents need to reconsider their governance plan specifically around intellectual property and data ownership to manage a platform’s open ecosystem and shared licensing models. For example, data governance was a key consideration in the implementation of Walgreens’ Connected Health platform to secure the full spectrum of patient data. - By embedding a collaboration culture to innovate and co-create with start-ups and entrepreneurs in the ecosystem, incumbents can develop viable platform businesses. Bank of New York Mellon runs NEXEN, an open-source, cloud-based technology platform that enables it to develop microservices in API format. NEXEN, together with private cloud and big data components, is expected to raise the bank’s bottom line by around 10 percent in 2017. Its success is attributed to an early cultural change transformation that attracted new millennial talent, encouraged employees to use design thinking, and effectively migrated legacy technology to the NEXEN platform.

- The successful platforms became so based on network effects, the large demand economies of scale where users create value for users. Note that the biggest firms occur in the U.S. or China, where there are large homogenous markets. So be aware of policies that introduce fragmentation. Policy makers should be setting policy that helps create the greatest value for the greatest number of people and reduce fragmentation of markets. That will allow the large network effects to emerge.

- The national economic, business and regulatory environment in which digital platform businesses are founded determines how they develop and scale. Each country — driven by its city or regional clusters — appears to be exporting its own local competitiveness to the global platform economy. For example, the New York area is home to a high number of FinTech unicorn platforms as a natural progression of its strength in traditional financial services. Yet, five common success factors stand out:

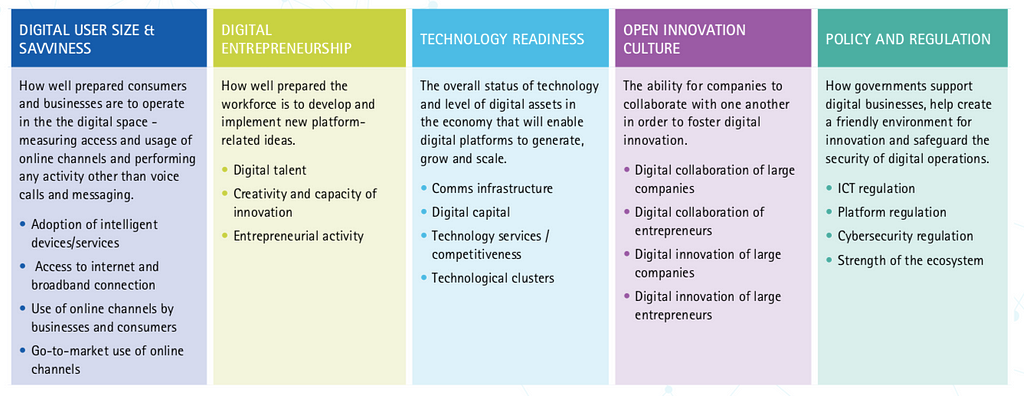

1. Digital user size and savviness: The scale of the market matters; countries with a large installed digital base and uniform culture, language and regulations have a competitive edge.

2. Digital talent and entrepreneurship: Science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), entrepreneurial and creative skills are fundamental in enabling digital innovation. It is vital for governments to focus on nurturing these skills in their educational priorities, and for businesses to locate themselves based on talent pool availabilities.

3. Technology readiness: The status of technology and digital assets, including levels of connectivity and investment in next-generation technologies — such as the industrial internet and artificial intelligence — will influence platform generation, growth and scale.

4. Open innovation culture: Increasingly, innovation — embedded in business culture and in how the platform operates — relies on organizations partnering with developers or service complementors. Large companies need to design new open organization structures, processes and governance to manage platforms’ open ecosystems, while embedding a collaboration culture. Governments need to foster innovation hubs, bringing together universities, laboratories, start-ups and large businesses.

5. Adaptive policy and regulation: Rapid speed of change demands proactive and participative policy making, working jointly with platform players on complex areas, such as data privacy, blockchain or cybersecurity.

Unlock trapped value with digital platforms

- Entrepreneurs, incumbent large companies and policy makers all have a role to play to orchestrate a vibrant platform economy.

- Platform disruption is not new. In the nineteenth century, the new technologies of electricity and steel smelting supported the development of the platforms of the day: factories. These new platforms united workers, producers, suppliers and distribution channels in ways that released value that was trapped in pre-existing forms of production. New ecosystems unlocked that value by improving the efficiency and scale of manufacturing. And those same ecosystems also enabled the innovation that resulted in the variety of goods that changed not just industry, but wider society.

- Today’s platforms are enabled by new digital technologies. Their ecosystems also involve great scale, bringing together customers, producers and innovators. Beyond scale, digital platforms use data to create value in new ways, resulting in entirely new products and services.

- Just as in the early days of factories, a proliferation of platforms will result in high levels of failure and consolidation. And just as in the era of industrialization, some economies will outperform others due to the enabling factors they have put in place.

- Our analysis of platform critical success factors shows that companies can begin to use digital technologies to release the trapped value now residing in the new ecosystems and markets that platforms are creating. But business leaders, entrepreneurs and policy makers must recognize the wider significance of digital platforms that will not merely create new opportunities for individual businesses, but transform entire sectors and economies. Platforms will reshape the way we produce, consume and do business. And, as history has shown us, today’s digital platforms can open up the potential for small businesses to reshape the industrial landscape.

- The task ahead is not just reimagining new business models and markets, but also appreciating the role of digital platforms in the transformation of economies worldwide.

- Network effects are sometimes referred to as “Metcalfe’s Law” or “network externalities.” But don’t let the dull names fool you — this concept is rocket fuel for technology firms. Bill Gates leveraged network effects to turn Windows and Office into virtual monopolies and in the process became the wealthiest man in America. Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, Sergey Brin and Larry Page of Google, Pierre Omidyar of eBay, Andrew Mason of Groupon, Evan Williams and Biz Stone of Twitter, Nik Zennström and Janus Friis of Skype, Steve Chen and Chad Hurley of YouTube, all these entrepreneurs have built massive user bases by leveraging the concept. When network effects are present, the value of a product or service increases as the number of users grows. Simply, more users = more value. Of course, most products aren’t subject to network effects — you probably don’t care if someone wears the same socks, uses the same pancake syrup, or buys the same trash bags as you. But when network effects are present they’re among the most important reasons you’ll pick one product or service over another. You may care very much, for example, if others are part of your social network, if your video game console is popular, and if the Wikipedia article you’re referencing has had prior readers. And all those folks who bought HD DVD players sure were bummed when the rest of the world declared Blu-ray the winner. In each of these examples, network effects are at work.

Not That Kind of Network

- The term “network” sometimes stumps people when first learning about network effects. In this context, a network doesn’t refer to the physical wires or wireless systems that connect pieces of electronics. It just refers to a common user base that is able to communicate and share with one another. So Facebook users make up a network. So do owners of Blu-ray players, traders that buy and sell stock over the NASDAQ, or the sum total of hardware and outlets that support the BS 1363 electrical standard.

KEY TAKEAWAY

- Network effects are among the most powerful strategic resources that can be created by technology-based innovation. Many category-dominating organizations and technologies, including Microsoft, Apple, NASDAQ, eBay, Facebook, and Visa, owe their success to network effects. Network effects are also behind the establishment of most standards, including Blu-ray, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth.

Where’s All That Value Come From?

- The value derived from network effects comes from three sources: exchange, staying power, and complementary benefits.

Exchange

- Facebook for one person isn’t much fun, and the first guy in the world with a fax machine didn’t have much more than a paperweight. But as each new Facebook friend or fax user comes online, a network becomes more valuable because its users can potentially communicate with more people. These examples show the importance of exchange in creating value. Every product or service subject to network effects fosters some kind of exchange. For firms leveraging technology, this might include anything you can represent in the ones and zeros of digital storage, such as movies, music, money, video games, and computer programs. And just about any standard that allows things to plug into one another, interconnect, or otherwise communicate will live or die based on its ability to snare network effects.

Exercise: Graph It

- Some people refer to network effects by the name Metcalfe’s Law. It got this name when, toward the start of the dot-com boom, Bob Metcalfe (the inventor of the Ethernet networking standard) wrote a column in InfoWorld magazine stating that the value of a network equals its number of users squared. What do you think of this formula? Graph the law with the vertical axis labeled “value” and the horizontal axis labeled “users.” Do you think the graph is an accurate representation of what’s happening in network effects? If so, why? If not, what do you think the graph really looks like?

Staying Power

- Users don’t want to buy a product or sign up for a service that’s likely to go away, and a number of factors can halt the availability of an effort: a firm could bankrupt or fail to attract a critical mass of user support, or a rival may successfully invade its market and draw away current customers. Networks with greater numbers of users suggest a stronger staying power. The staying power, or long-term viability, of a product or service is particularly important for consumers of technology products. Consider that when someone buys a personal computer and makes a choice of Windows, Mac OS, or Linux, their investment over time usually greatly exceeds the initial price paid for the operating system. A user invests in learning how to use a system, buying and installing software, entering preferences or other data, creating files — all of which mean that if a product isn’t supported anymore, much of this investment is lost.

- The concept of staying power (and the fear of being stranded in an unsupported product or service) is directly related to switching costs (the cost a consumer incurs when moving from one product to another) and switching costs can strengthen the value of network effects as a strategic asset. The higher the value of the user’s overall investment, the more they’re likely to consider the staying power of any offering before choosing to adopt it. Similarly, the more a user has invested in a product, the less likely he or she is to leave.

- Switching costs also go by other names. You might hear the business press refer to products (particularly Web sites) as being “sticky” or creating “friction.” Others may refer to the concept of “lock-in.” And the elite Boston Consulting Group is really talking about a firm’s switching costs when it refers to how well a company can create customers who are “barnacles” (that are tightly anchored to the firm) and not “butterflies” (that flutter away to rivals). The more friction available to prevent users from migrating to a rival, the greater the switching costs. And in a competitive market where rivals with new innovations show up all the time, that can be a very good thing!

How Important Are Switching Costs to Microsoft?

- “It is this switching cost that has given our customers the patience to stick with Windows through all our mistakes, our buggy drivers, our high TCO [total cost of ownership], our lack of a sexy vision at times, and many other difficulties […] Customers constantly evaluate other desktop platforms, [but] it would be so much work to move over that they hope we just improve Windows rather than force them to move. […] In short, without this exclusive franchise [meaning Windows] we would have been dead a long time ago.”

- “Microsoft: ‘Would Have Been Dead a Long Time Ago without Windows APIs,”

Complementary Benefits

- Complementary benefits are those products or services that add additional value to the network. These products might include “how-to” books, software, and feature add-ons, even labor. You’ll find more books on auctioning that focus on eBay, more video cameras that upload to YouTube, and more accountants that know Excel than those tareted at any of their rivals. Why? Book authors, camera manufacturers, and accountants invest their time and resources where they’re likely to reach the biggest market and get the greatest benefit. In auctions, video, and spreadsheet software, eBay, YouTube, and Excel each dwarf their respective competition.

- Products and services that encourage others to offer complementary goods are sometimes called platforms. Allowing other firms to contribute to your platform can be a brilliant strategy because those firms will spend their time and money to enhance your offerings. Consider the billion-dollar hardware ecosystem that Apple has cultivated around the iPod and that it’s now extending to other iOS products. There are over ninety brands selling some 280 models of iPod speaker systems. Thirty-four auto manufacturers now trumpet their cars as being iPod-ready, many with in-car docking stations and steering wheel music navigation systems. Each add-on enhances the value of choosing an iPod over a rival like the Microsoft Zune. And now with the App Store for the iPhone, iPod touch, and iPad, Apple is doing the same thing with software add-ons. Software-based ecosystems can grow very quickly. In less than a year after its introduction, the iTunes App Store boasted over fifty thousand applications, collectively downloaded over one billion times. Less than two years later, downloaded apps topped ten billion.

- These three value-adding sources — exchange, staying power, and complementary benefits — often work together to reinforce one another in a way that makes the network effect even stronger. When users exchanging information attract more users, they can also attract firms offering complementaryproducts. When developers of complementary products invest time writing software — and users install, learn, and customize these products — switching costs are created that enhance the staying power of a given network. From a strategist’s perspective this can be great news for dominant firms in markets where network effects exist. The larger your network, the more difficult it becomes for rivals to challenge your leadership position.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Products and services subject to network effects get their value from exchange, perceived staying power, and complementary products and services. Tech firms and services that gain the lead in these categories often dominate all rivals.

- Many firms attempt to enhance their network effects by creating a platform for the development of third-party products and services that enhance the primary offering.

One-Sided or Two-Sided Markets?

Understanding Network Structure

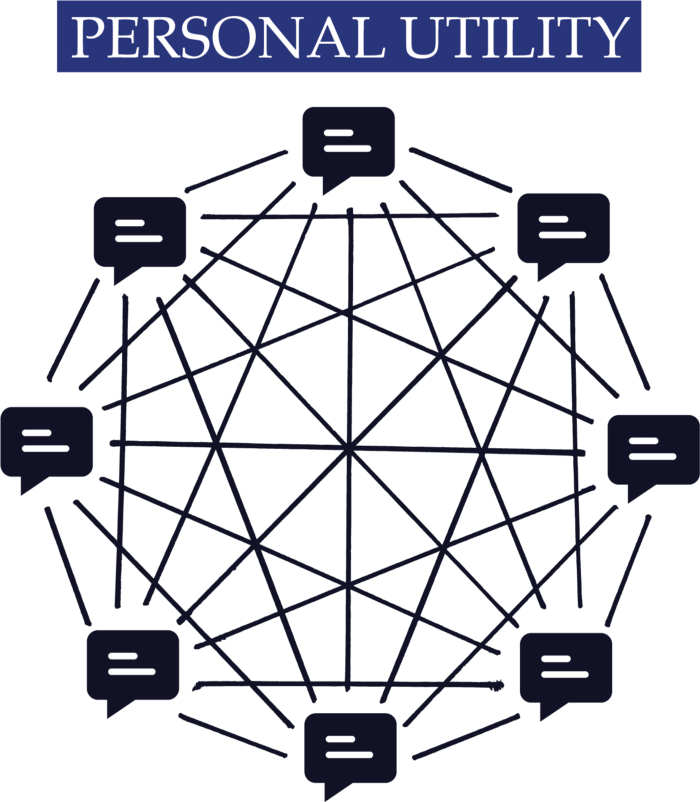

- To understand the key sources of network value, it’s important to recognize the structure of the network. Some networks derive most of their value from a single class of users. An example of this kind of network is instant messaging (IM). While there might be some add-ons for the most popular IM tools, they don’t influence most users’ choice of an IM system. You pretty much choose one IM tool over another based on how many of your contacts you can reach. Economists would call IM a one-sided market (a market that derives most of its value from a single class of users), and the network effects derived from IM users attracting more IM users as being same-side exchange benefits (benefits derived by interaction among members of a single class of participant).